This project started out as a personal investigation into the climate crisis and what we can (and should) be doing about it. The aim was to document and share a path through this topic rather than to offer anything original.

It is heavily inspired and influenced by David Mackay’s Sustainable Energy without the Hot Air which we read soon after it came out in 2008. This brilliant book is still a go-to despites its age.1 In particular, his factual approach and the “you only understand what you can create for yourself” mentality. Of course, this effort is much more modest in scope (and capacity). Nevertheless, we hope it proves of value.

Motivating questions

- What is actually happening? For example:

- How much CO2 (and GHGs) are we emitting? How much is that relative to the past?

- What impact has there been on the temperature and the climate? What is likely future impact?

- What impact has there been on the planet and on humans — already and in the future?

- What’s causing this? For example, what is the role of different countries and different energy sources in generating CO2 and GHGs?

- Also what actors — countries, corporations etc — are behind this, and who is blocking change?

- What can we do about all of this?

- What is the case for action?

- What policies can we use to reduce emissions?

- What cleantech do we need, what investment do we need?

- What kind of mitigation or adaptation is possible?

- Is it “too late” to stop dangerous warming?

- What is being done? By whom?

- What is to be done (and now)?

Table of Contents

Conceptual Model

We use the following rough conceptual model for thinking about the climate crisis and policies to address it.

1. Human Processes (e.g. energy production, travel etc)

|

| <--- Policy (emissions controls, cleantech)

|

V

2. Green House Gases (GHG)

|

| <--- Sequestration

|

V

3. Climate Change (temperature, sea level, weather patterns)

|

|

|

V

4. Direct Impact (storms, ecosystem changes etc)

|

| <----- Policy (mitigation, adaptation, transfers)

|

V

5. Indirect Impact (homes lost, hurricance damage)

|

| <----- Policy (rebuilding, compensation)

|

V

6. Impact on Lives (measured in well-being $)

Reading IPCC reports, it appears that the greatest efforts — and the greatest certainty — is around steps two and three: documenting GHG emissions and their link to climate change.

My intention, for the present, is to focus on these: to gather the best summary data on these two areas and set it out in a simple and compelling way.

Later one could expand in two directions. First, backwards into the causes of GHG. In particular, what is the composition of energy production and use and how could that change.

Second, forwards into the impact. The impacts is ultimately what matters but also the area where there is the greatest uncertainty. Right now we could focus on some of the things that have already been happening: the increasing number of forest fires, the growing number of extreme weather incidents etc. Just documenting them and assigning some probability score would be useful.

Situation

Temperatures are rising

Global temperatures have been rising, especially since 1980, relative to historical norm and this seems to be accelerating.

The Carbon Budget

Fn in IPCC 1.5 chapter 2 https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-2/

Chapter 1 has assessed historical warming between the 1850–1900 and 2006–2015 periods to be 0.87°C with a ±0.12°C likely (1-standard deviation) range, and global near-surface air temperature to be 0.97°C. The temperature changes from the 2006–2015 period are expressed in changes of global near-surface air temperature.

Historical CO2 emissions since the middle of the 1850–1900 historical base period (mid-1875) are estimated at 1940 GtCO2 (1640–2240 GtCO2, one standard deviation range) until end 2010. Since 1 January 2011, an additional 290 GtCO2 (270–310 GtCO2, one sigma range) has been emitted until the end of 2017 (Le Quéré et al., 2018).

What do we need to do?

What emissions reductions do we need?

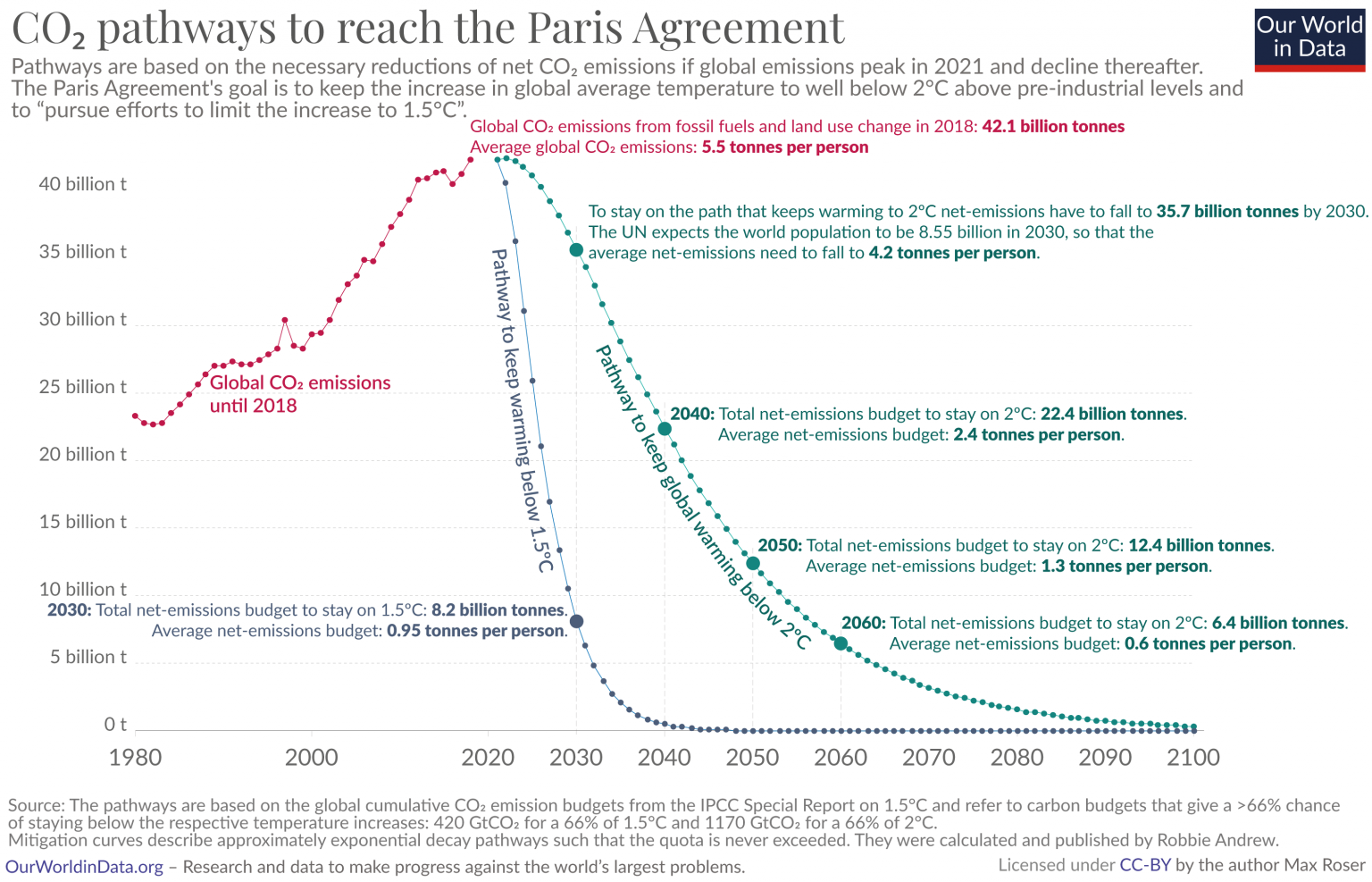

We have a remaining carbon budget of max 420 GtCO2 (from 2018). This implies reducing emissions to net zero by 2050 assuming rapid reductions now — or much earlier if significant reductions dont’ start now.

As of 2021, we are not following that pathway and hence net zero should already be earlier and reductions must start now and fast.

From the IPCC 1.5 report in 2018: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-2/

Cumulative CO2 emissions are kept within a budget by reducing global annual CO2 emissions to net zero. This assessment suggests a remaining budget of about 420 GtCO2 for a two-thirds chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C, and of about 580 GtCO2 for an even chance (medium confidence). The remaining carbon budget is defined here as cumulative CO2 emissions from the start of 2018 until the time of net zero global emissions for global warming defined as a change in global near-surface air temperatures. Remaining budgets applicable to 2100 would be approximately 100 GtCO2 lower than this to account for permafrost thawing and potential methane release from wetlands in the future, and more thereafter. These estimates come with an additional geophysical uncertainty of at least ±400 GtCO2, related to non-CO2 response and TCRE distribution. Uncertainties in the level of historic warming contribute ±250 GtCO2. In addition, these estimates can vary by ±250 GtCO2 depending on non-CO2 mitigation strategies as found in available pathways. {2.2.2, 2.6.1}

Staying within a remaining carbon budget of 580 GtCO2 implies that CO2 emissions reach carbon neutrality in about 30 years, reduced to 20 years for a 420 GtCO2 remaining carbon budget (high confidence). The ±400 GtCO2 geophysical uncertainty range surrounding a carbon budget translates into a variation of this timing of carbon neutrality of roughly ±15–20 years. If emissions do not start declining in the next decade, the point of carbon neutrality would need to be reached at least two decades earlier to remain within the same carbon budget. {2.2.2, 2.3.5}

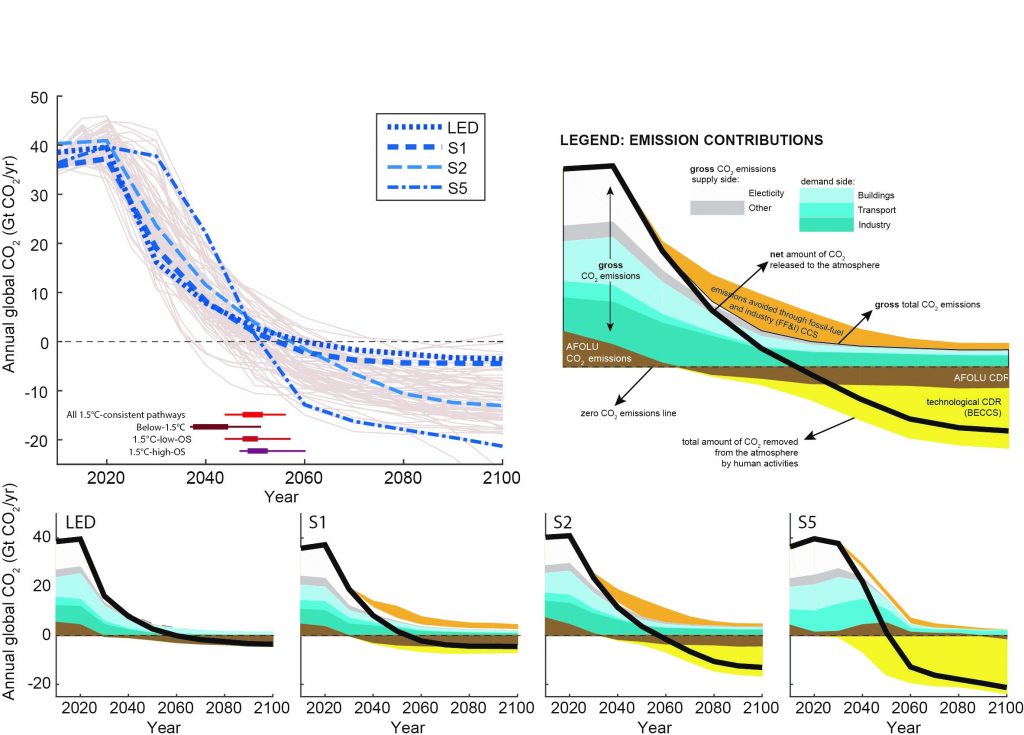

Here’s a key diagram from IPCC SR15:

Note that reading this carefully it is clear that electricity (white area under the graphs) is net-zero much earlier than 2050 by 2030 or 2040. That means a complete transition to net zero green energy in the next decade! This intuition is borne out by this next figure:

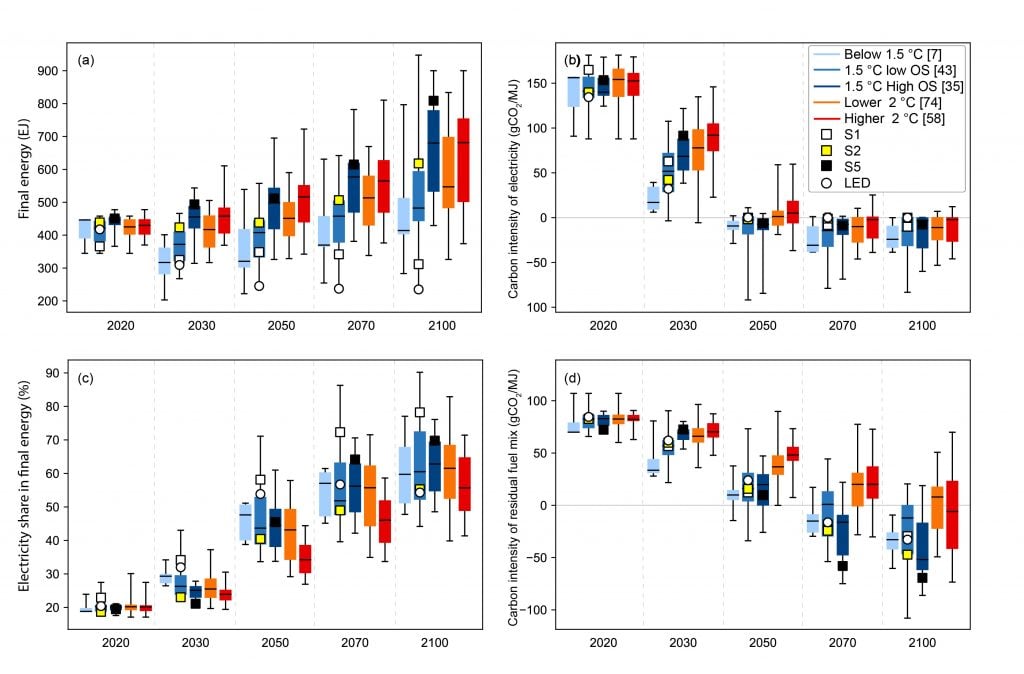

Fig 2.14: Decomposition of transformation pathways into (a) energy demand, (b) carbon intensity of electricity, (c) the electricity share in final energy, and (d) the carbon intensity of the residual (non-electricity) fuel mix

If you focus on light blue and dark blue one sees that electricity has carbon intensity at or close to zero by 2030. Note that most models don’t assume 100% renewable but rather increasing renewable plus carbon capture and storage for fossil fuel plants still runing. (“The share of energy from renewable sources (including biomass, hydro, solar, wind and geothermal) increases in all 1.5°C pathways with no or limited overshoot, with the renewable energy share of primary energy reaching 38–88% in 2050”)

Another one from OWID

Source: fn 10 in https://ourworldindata.org/worlds-energy-problem

What options are there for doing that?

- Energy

- Food

- …

TODO: sources of emissions

- transportation (29%), electricity (28%), industry (22%), commercial and residential (12%), and agriculture (9%) (https://www.climatecentral.org/gallery/graphics/emissions-sources-2020#:~:text=As%20defined%20by%20the%20Environmental,%2C%20and%20agriculture%20(9%25).)

- https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data - sourced from IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change

Which are feasible?

Can we get enough from Solar (alone)?

See https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/energy/publication/solar-photovoltaic-power-potential-by-country

Reading List

See Zotero bibliography: https://www.zotero.org/groups/1488090/life-itself/collections/XA8U7WGT

Sustainable Energy without the Hot Air by David Mackay - Brilliant book, still a go-to even though published in 2008.

Project Drawdown - see also https://github.com/datasets/awesome-data/issues/329

https://www.unep.org/interactive/emissions-gap-report/2020/ - basically things are not looking good!

The world is still heading for a catastrophic temperature rise in excess of 3°C this century – far beyond the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C.”

…

So far, action on a green fiscal recovery has been limited. Around one-quarter of G20 members have dedicated shares of their spending, up to 3 per cent of GDP, to low-carbon measures. For most others, spending has mostly been high-carbon or neutral.

- Mackay was unable to update his book due to his tragically early death from cancer in 2016. One part of the effort here could be to help update his book.↩